I’ve been discussing dementia care with some experts this week, and the advice that comes to me again and again as I research this topic is to have the important conversations early. I think we all tend to put off thinking about old age, because we are deep down scared of what might happen. And longevity can bring disability and limitations. But it doesn’t have to bring sadness. Retirement doesn’t have such negative connotations. We all hope that at some time in our lives we might be able to change gear, enjoy life a bit more and work a bit less.

In order to be able to look forward to a full life, I think it is important to understand how we change with age and to plan for those different situations as they arise.

It is worth going back to Shakespeare’s examination of the seven ages of man, to understand how we tend to categorise age – and perhaps question some stereotypes.

My analysis of the melancholy Jaques’ speech is that he all too quickly skips from youth to age. But when you realise that Shakespeare was probably in his early thirties when he wrote these lines, you realise that he’s speaking from personal experience when he speaks of youth, love and brawling and then of observation when he starts to talk about the justice, the lean and slippered old man declining into childishness and thence oblivion.

We all tend to think of ourselves like this. We were young; we are going to become old. We forget that somewhere in between lies many years of challenge, vigour and enjoyment, that won’t be exactly the same as youth, but will have much to commend it. Planning for longevity is a tricky thing to do, because none of us likes to contemplate change, especially if that change might be for the worse. But just as most of us take out insurance against flood, fire and theft, hoping we will never need them, we should think about life in the same way.

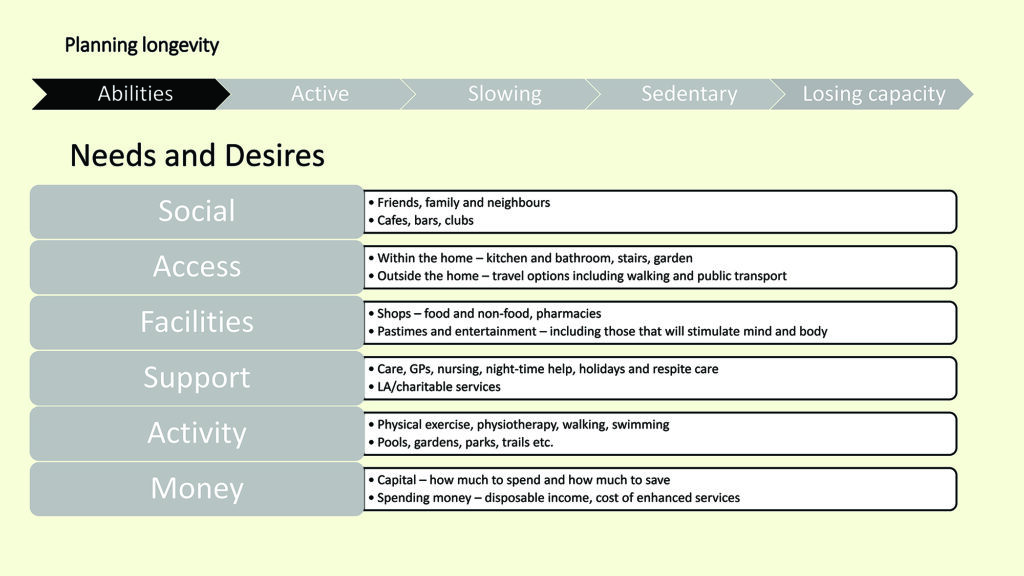

I’ve reproduced below one of the tools from the book, Glorious Summer, that is designed to help you think about your future, and the future of those around you. Along the top there is a progression from active to inactive and down the side some headings to help you think about potential needs at each stage including physical, financial and social requirements. Please note that there is nothing to say that a progression from active to inactive is necessarily a one-way-street. We can improve and need to plan for the ebb and flow of abilities that is a feature of life. We’ve all been bedbound for a day or two. Next time you find yourself having a duvet day, take a little time to think about how you’d feel if this was your lot for a month, or six months. If you break your leg and can’t get up from the chair without help, think about how a more permanent version of that disability would feel and more importantly – how you would adjust to reconcile yourself to the disability.

The most difficult question of all is what will you do if your partner dies, or is seriously incapacitated. I am astonished that more couples don’t ask themselves these questions. The result of a discussion raises all sorts of questions from, Where is the stop-cock? to What’s the joint account password? In most relationships one person will take on certain tasks and the other will pick up the slack elsewhere. But in reality, it is far more sensible to make sure that both parties in a relationship know a little about everything. That means where things are, how to cook, where the money comes from and how to get about.

Changes are best made sooner than later. But if serious illness rears its head, do start to discuss the implications quickly. You won’t feel like it later on.

I am astonished how many people decide to retire to the country, not realising that isolated villages are one of the last places you should consider growing old, unless you are as rich as Croesus. Even two people may find isolated living difficult. Reduce that to one person, remove the car, or the ability to walk about and simply existing becomes very difficult. And while in theory everything can arrive by mail, the paucity of experience that this lifestyle brings is certainly not to my tastes. As we get older proximity to services, hospitals and carers all might become important – very few of these facilities are found in isolated spots.

However, as well as considering functional necessities like the proximity of an A&E department, there is a far more pleasant list of requirements that might interest us. Being able to continue wild swimming, shopping, baking, music, painting or cycling can add to the pleasures of old age. Many of these pass-times may eventually become too difficult, but while you can do those things, plan to be able to do them easily. They will all help you maintain a healthy body and mind.

In choosing where to live, have in mind safety, access to open space and access to facilities. Living at ground level with a garden, or having a sunny balcony would be a priority for me. If you like playing bridge, is there a bridge club? If you like gardening, is there a community garden nearby? Crystal ball gazing is hard, and your tastes and requirements will change in quite unexpected ways. Try to assess whether there is enough access to different facilities to keep you happy now, as well as occupying you in a different a future.

Even if you are the older one now, don’t assume that your partner will outlive you and care for you. Neither should you assume that a sibling, a good friend or children will always be available. They have their own lives to lead. Living independently can help us live longer, but even the most solitary person can become dependent by virtue of disability, or because they suffer from anxiety and loneliness. Having early discussions with trusted friends, partners and relatives will all reveal new ideas and different ways of thinking about things. Ask your friends to be critical and questioning. You need to accept that their priorities will be different to yours, but needs can change in quite unexpected ways. Building in flexibility may be an important aspect of your forward plan.

Like Shakespeare, you might want to think about longevity in stages, but remember that none of these stages are necessarily irreversible. Ageing is not linear. Thinking about a future need not be frightening or threatening. Approach the issue with enjoyment top of your wish list, followed by practicality and spiced with a little originality. No one is judging you. There is no right or wrong way to approach the issues. If you decide to sell up and join a commune in Kathmandu – good for you!

Four stage discussion process

Stage 1

Let your imagination run riot. If you want to spend the glorious summer of your longevity playing chess, sitting in an Adirondack chair, overlooking a Caribbean beach – then now is the time to plan it out. If you seek a modern town-house near to the opera, go for it.

Stage 2

Discuss your idea with trusted friends and neighbours. Ask them to be critically supportive.

Stage 3

Modify your ideas to take account of practicalities, such as finance. This is the stage when you’ll need a lot of ingenuity and inventiveness to realise your dreams at an affordable rate.

Stage 4

Then and only then check your ideas against the checklist below.

Download Longevity planning Chart Here

Download Longevity planning Chart Here

Now you have a handy chart you can populate it with anything that is important to you. For example, if you’ve always enjoyed the mountains, then now is the time to incorporate mountains into your longevity plan. Remember that these stages won’t occur neatly and in a linear fashion. An accident or stroke can induce mental incapacity overnight. Similarly, just because at one stage of your life you may find yourself in a wheelchair, there is no reason to conclude that this will always be the case. Test your ideas forwards and backwards, progressing to a better state or regressing to become less able.

Time is a difficult one to judge. If you decide you’ll need to live in a care home at the end of your life, work out how many years you can afford to do so. Remember that old age doesn’t last forever. High-cost solutions can be afforded for a time. According to some 2017 market research the average length of time in a care home is 30 months, and the average cost is approximately £32,000 per year [LaingBuisson, Care of older people: UK market report, May 2017, p. xxiii]

There is no perfect answer to your longevity plan. But it is worth thinking it out, with your partners and loved ones, before you get too far down the line. Many people leave this type of planning until too late in life. By the time they find themselves needing to move, or requiring more care, it can feel as if the options are too limited. Planning will mean, at the very least, that you have some control over the sort of situation in which you spend your latter days. And, instead of dreading old age, you can look forward to reaching life’s sunny uplands.

I’d really appreciate your thoughts and tips about this blog. Talking about an uncertain future is probably one of the most difficult conversations you’ll ever have to have. If you’ve done this, tell me how it went, by entering a comment in the section at the base of this page.

This year I shall be maintaining a weekly blog, covering pre-publication excerpts from the book as well as a series of articles about the science and the scientists who have unlocked the secrets of longevity. Please register your interest by clicking on the mailing list below.

A beta reader is a test reader of an unreleased work (similar to beta testing in software), who gives feedback to the author, from the perspective of an average reader. If you’d like to help me get this book as good as it can be, I’d love to hear from you. The chapters will be ready from June onwards. I’m sorry there is no fee for this work, except a free copy of the finished book and an acknowledgement. This is not a commercial exercise. Say Tomato, the publisher of the book and of the website is run as a self-financed social enterprise. I shall be eternally grateful. Any profits from Glorious Summer will be directed into Say Tomato work for women over 40.

Contact me directly wendy@wendyshillam.co.uk if you are interested, giving a brief description of yourself and your reading experience. (It doesn’t matter if you haven’t done any beta reading before – avid readers make the best beta readers.) Thank you.

Wendy Shillam

Trained in environmental and bio-sciences, Wendy Shillam is a registered clinical nutritionist, specialising in longevity. She is the founder of the social enterprise Say Tomato! that provides free and trusted weight loss advice for women over forty. This part of the blog is a precursor to publication of her book, Glorious Summer – the secrets of longevity. You can read about it here.

Hi Wendy,

This is thought-provoking stuff. My wife often says she wouldn’t know where to begin, in terms of understanding our household bills, etc. if something happened to me. Instead of me basking in assumed indispensability I see now we need to deal with this.

I thought too the bit about retiring to the country very helpful. While thoughts of a late bucolic idyll or seclusion in a converted lighthouse may appeal to the romantic heart we need to temper our spirit of adventure with the plain fact of our mortality. And imagine the price a Stannah stairlift?

On a more serious note, I retired a couple of years ago from the civil service, and while they have a helpful retirement package and a day-course to attend, we didn’t talk about the ideas you are putting out here, which I think would have been of more interest and relevance.

Also, re dementia, have you seen Wendy Mitchell’s book, “Somebody I Used to Know”, about her experience with coming to terms with early onset dementia? She also has an excellent blog “Which me am I today?”

Thanks for your comments Alex. ALways pertinent and thoughtful. It looks like an interesting book. I found a couple of reviews online there’s one here from The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/28/wendy-mitchell-somebody-i-used-to-know-interview-dementia

I’m seriously thinking of offering my services to retirement courses – if anyone has any ideas?

Thanks for this article! You raise very good points and the exercise is something to revisit time and again.

I agree, we tend to underestimate our abilities. Swimming in particular is something we can do even if we are very frail. Even bobbing about in a pool is good exercise.